It was the night before my dad’s funeral and I was in chosen to write his eulogy. I can’t say that my dad would’ve been proud of how it was produced, but I’m positive he would’ve understood it. Apples don’t fall from the tree.

Another cliche: “No family is normal.” You know the saying. The Penners are no exception to this rule. We’re screwed up just like everyone else is.

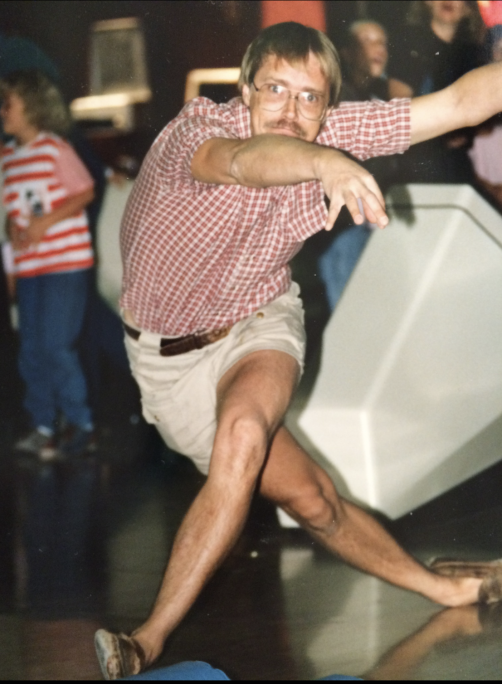

The night before the funeral, come sunset, the family splintered off. The older crowd went home. My brothers, a couple cousins, a few friends, and I all went to the pool hall that my dad used to take us to. I even brought his cue. It was a weird scenario. It’s not that we weren’t sad, of course we were, but we still had a really fun night together. It’s what my dad would’ve wanted. Never have we all been together at once. It was an anomaly in the sense that my dad died and that’s what had made this possible. We shot pool, dicked around, told stories of him, and in my dad’s memory (before he got clean) we drank Coors Light and Vodka Tonics. Grey Goose, of course. For such a bum, he could be a real snob.

As the night grew late, we fractured once again. I’m sure the others went to bed. I didn’t go home, though, and my cousin, Chris, came with me. He’s my best friend. We call him him meemie seeko. Long story, but it means “cat piss.” He calls me the same. It’s from a Jonathon Taylor Thomas movie we watched as kids. Although he’s from my mom’s side, Chris loved Uncle Randy and Uncle Randy loved Chris. In any case, we called an Uber and went to the tattoo shop.

I have a few tattoos. Twenty-one to be exact. In the tat world, it is very nerdy/shunned to know your exact number (although I bet a vast majority of them do), but that’s mine— 21. I know this because every time I see my little niece Madison, she asks me and we count. Occasionally when I’m out and about I’ll get that same question. However, the more common question is: “What do they mean?” 99 times out of 100, I’ll say, “They don’t mean anything.” For the most part, that’s true. Only two really have a meaning.

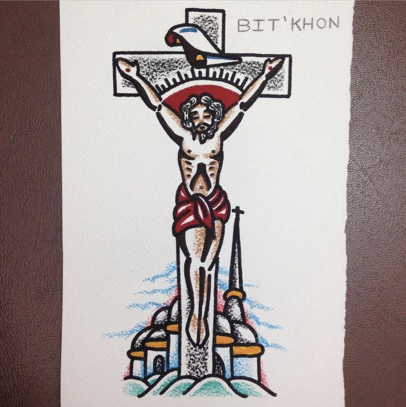

There’s the obvious one. Above my left elbow is a red heart that says “MOM”across a banner in black. Sometimes I mess with people and tell them it’s a for me, upside-down “WOW” heart. She hates every tattoo except for that one. The other meaningful one is on my inner right bicep. It’s the one I got that night, before the funeral. For him. My dad used to have the exact painting, sitting on the night stand at hospice. It depicts the crucifixion of Christ. So that’s why I tend to avoid the question, because when meeting someone for the first time, it’s better not to open with, “I got this one for my dead dad.”

Towards the end of his life my dad got real religious, which is rather ironic. He got kicked out of church when he was eleven after constantly challenging his Sunday school teacher and pulling various pranks. Part of him wished he was Jewish. He was fascinated by their history and he was always one for the underdog, especially if they were persecuted. When he died, I inherited his golden Star of David. Usually the necklace hangs from a nail above my headboard next to his picture, but sometimes I actually put it on and wear it. So in his heart he was Jewish, but philosophically he was Christian. It’s nonsensical, even more so contradictive, I know, but so was he. He was a walking contradiction. For not having his own life in line, he was the wisest man I knew. The problem with some wise men is that they seldom adhere to their own advice. Part of me thinks he held these contradicting convictions to make sure his name would be on the list when he showed up to the red carpet of heaven’s gates. In his mind you couldn’t be more money than being a Jew who believed in a resurrected Christ.

One day, on the last trip home from the hospital, before he went into hospice, we stopped at his favorite local Burger Joint- Colorado Grill. He was obsessed with their milkshakes. He had one every day. Sometimes I thought it was if that vanilla shake was some kind of weird security blanket that kept him anchored to this side of death. While my brother ran in to grab the food, my dad told me that he wanted a painting of Jesus’ crucifixion to be done by my friend, whom, once upon a time, my dad took in my while his mother was going through her own thing. I remember one night when she came over and they got into an argument on the front porch. One of them called the other one an alcoholic and the other got mad. What a ridiculous conversation that was. Nothing offends an alcoholic more than telling them the truth, especially coming from an alcoholic. In any case, it was from her son that my dad commissioned the painting- Christ nailed to the cross, blue clouds in the background. On the painting above Jesus’ head is an inscription that reads “BIT ‘KHON.” He was obsessed with that saying, although for some reason I can’t remember what it meant, if it meant anything at all. The same dude who bought him the Star of David necklace in Jerusalem taught him the term, but by the time it made it to my dad, then through me, and finally to my friend, I imagine the spelling is off and we missed the whole point. Again, if my dad was anything, it was unconventional, so above Christ being crucified is a Jewish-ish saying.

I must’ve known that I was going to get it tattooed that night because I took the painting with me to the pool hall and then to the tattoo shop. I remember the tattoo hurting (most of them do), drinking Coors Light tall cans from the liquor store on the corner, and the three of us telling stories about my dad. The next thing I remember is being shit-faced in the back of an Uber. And tired. Horribly tired. Physically and mentally. We got home about two, which meant that I had fucked myself. My cousin got to go to sleep, but I couldn’t. I still had to write a eulogy that I hadn’t even started. It was 2:30 a.m. when my cousin passed out on the extension of the couch, with me on the other side, sitting before an empty page underneath the hushed lamp light. The house was silent and dark.

With a eulogy, at least in my opinion, the goal is to celebrate the departed’s life as truthfully as you can. Actually, it’s kind of the same formula for a best man’s speech. It helps to be funny. You can even make fun of the dude, but in the end you gotta tell everyone what a great guy he was. Tell the truth by all means, but one must know where the line lies between the truth and too much of it. If you’re going to err, err on the side of caution. I once saw a wedding speech where the best man talked about the groom’s last marriage and how he hoped “this next one would actually last.” It was because of this dipshit that I omitted a certain line from the eulogy. For example it would’ve been bad form to bring up the time when, five fourth of July’s ago, my mom, brothers, and I met in a parking lot and decided it was time for my dad to have his own “Come to Jesus Moment.” It was rehab or us.

I stayed up all night writing that thing. It was, in some respect, both the easiest and the hardest thing I’ve ever written. Hard because it was a eulogy for my dad. Remembering him and putting those memories on paper gave death a sobering sense of finality.

I had written him off a few years prior, but he did all he could to hang around. I hesitated to put my faith in someone who had let me down so many times in the past. It wasn’t until I had to be hospitalized for a month that we really became close again. He used to come sit with me every day. He in the chair by the door, me in the bed hooked up to a million wires. Little by little I started to forgive him and that’s when the healing began and we started to form a (new) bond.

A couple months after my stint in the hospital, it was my dad’s turn. The chemo could only slow the decay down so much. I did for him what he did for me. I showed up. I told him that it was going to be ok, that I was there for him, and that I loved him. In those few months, we had grown closer than we’d ever been and I started to know him on a deeper level. With that came understanding. That’s why the eulogy was easy to write. I knew him in a way that few other’s had.

When the sun started to shine through the living room windows, I started to sober up and put on the finishing touches. Then the full house started to stir and I jumped in the shower and tried to wash off the lasting effects of the alcohol. It worked until it didn’t.

At about 7 Josh came by the house to pick up Chris and me. Before getting in the car I turned to him and said, “I don’t know if I can do this.”

Josh tried to reassure me that I could go through with all this. “Of course you can,” he said, trying to convince me of something he didn’t understand.

“No. That’s not what I meant. Not exactly, anyway.” The shower helped in sobering me up, but did nothing for the hangover that started to creep in. “I don’t think I can get in that car. I don’t feel very well.”

In my years I have found that the best thing to do on the morning after a long night is to have another drink. I saw my dad perform this trick many times. The good ol’ hair of the dog remedy. I told Josh and Chris to give me a second. I walked into the house and snuck a tall can out of the refrigerator. In my mind’s eye, I hid it underneath my jacket from either my mother or my aunt. I came back outside and they looked at me like, what the fuck are you doing? It was the only way any of this was going to work. It worked until it didn’t.

In my new blue suit, I chugged that thing down. A few moments later, before getting into the car, I felt even worse. I just need a moment, I told them. That’s when my stomach started to toss and turn and I jumped to the bushes near the corner of the garage. Chris held my tie back while I puked on my shoes. Once I got it all out, I felt better physically, but emotionally I still felt sick. Ashamed. Guilty. I had spent the majority of my life trying not to become my father, yet here I was at 7 in the morning, downing a beer and puking on my new shoes before I gave his eulogy.

We drove to the church. It was a a few miles down the freeway from my mom’s house. I’d been there a couple times with my dad and I’ve been there a couple times with my friends. It was a great skate spot. We used to go skating there all the time. I remember pulling up to the parking lot and then I remember walking up the street, in the blazing heat, to the liquor store up and around the corner. I needed cigarettes. Not long after my whole family arrived, we started setting everything up for the reception- the food, the flowers, and the plastic silverware in the gym that had its basketball hoops retracted up towards the ceiling.

I have been the best man at both my brother’s wedding and gave both the speeches. I learned my lesson at the first one. Somewhere on the way to the reception I had lost the speech, so I rewrote the thing in 20 minutes while the party went on without me. This time my speech was packed away in my jacket pocket. I made sure. Checked a million times.

The priest, Father Carlos, kicked the funeral off. I was siting in the front row, listening to him give the opening statement. I was sweating through my white shirt under my jacket. I knew my turn was coming. The speech was good, that much I gave myself. But as far as spelling and grammar goes, I write at a third grade level. Those might seem like little things, but they can really fuck a speech up.

If I got one thing from my father, it is the way I communicate with people. Where the origin lies, I’m not sure, but I have a guess. Like my dad, I have seen some hard times, and since I’ve seen those, I put on a smile for the world as if I want to protect them from something I wish they’ll never be able to understand.

Another thing I got from my dad is my inability to remember names. When meeting someone, I’ll often go dumb-face… the second after I introduce myself I forget to listen for their name. Dale Carnegie would be disappointed. He says, “A person’s name is to that person, the sweetest, most important sound in any language.” I couldn’t agree more, but I’ve never been one for the name. Carnegie also said, I believe, quoting someone else, that people “may forget what you said, but they’ll never forget how you made them feel.” That was more in line with the philosophy that my father and I shared. We never forget how someone made us feel. We were more about the soul. Since he could never remember any of our friend’s names, he always referred to them as Bob. It was a term of endearment. He called all of my friends, all of my brother’s friends, the kid on the soccer team, etc… “Bob.” The girls were “Bobettes” In turn they referred to my father in the same way. Before he died, they used to ask me whenever I saw them, “How’s Bob doing?”

My memory has all the Bobs from my whole timeline sitting in the front row of the left pew. In reality, I think it was Chris, Josh, Brent, Chip, Ryan, Aaron, China, Paul, Ian, and I wanted to say Anthony, but I just talked to him and he told me that he wasn’t there. If it wasn’t for this group of Bobs sitting there, I don’t know if I could’ve finished it. It was them that I looked to when I choked up. It was if they had transfused me with courage to continue on. When I finished there was an applause and then I took a seat with all of them.

I love you, Bob.